in what ways did the rodney king event contribute to police reform

When a Simi Valley jury announced the "non guilty" verdicts in the case of four constabulary officers charged in the chirapsia of African American motorist Rodney Rex to a packed courtroom on April 29, 1992, Los Angeles erupted in a firestorm of anti-police protest. Annexation, burning, and violence lasted 6 days in what became the largest episode of civil unrest in American history.

For many beyond the country who watched television coverage, the Los Angeles rebellion, equally the issue has been called by some, exposed the persistent issues of racism, poverty, and inequality in American life.

With recent attending focused on police brutality, mass incarceration, and Black Lives Matter, the twenty-fifth anniversary of the 1992 uprising provides an opportunity to reflect on the meanings of race and justice in American society. Agreement the grievances that fueled the rebellion and the response of police enforcement and political officials offers of import lessons for how to empathise and reply to the current political moment and policing crisis.

On March three, 1991, four LAPD officers beat Rodney King using aluminum batons and Tasers. Unbeknownst to the officers, a bystander filmed the chirapsia and gave the tape to a local news station. The video, which circulated on television around the world, provided startling evidence of the LAPD'southward excessive use of force and confirmed complaints of police brutality made past black and Latino residents during the 1970s and 1980s.

George Holliday's footage of Rodney King being beaten by police in 1991 (left), and King's injuries (right).

In response to the public outcry surrounding the beating, Mayor Tom Bradley, who had been elected city's first African American mayor in 1973, formed the Independent Committee on the Los Angeles Police Department on April ane, 1991. Bradley appointed one-time FBI Director Warren Christopher to atomic number 82 the investigation of the LAPD's policies, practices, and culture.

The Christopher Commission report, published in July 1991, pulled few punches. Information technology condemned the LAPD'due south discriminatory practices and revealed a racist civilisation inside the section that contributed to the use of excessive force in black communities.

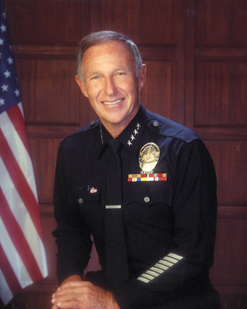

The commission recommended the resignation of Chief of Police Daryl Gates, the adoption of community policing, new training and supervisory procedures, and a series of structural reforms to make the department more answerable to the mayor and Lath of Police Commissioners. In early June 1992, voters overwhelmingly passed Charter Amendment F, which reformed the Urban center Lease by strengthening civilian oversight of the police department and limiting the tenure of the main of police to two five-year terms.

Yet, these measures were too picayune and too belatedly.

The trial of the 4 LAPD officers, held in the almost all-white suburban enclave of Simi Valley, became a judgment on the state of policing, racism, and the criminal justice arrangement in Los Angeles and the nation. The jury, equanimous of x whites, ane Latino, and one Filipino-American, included no African Americans. After the declaration of the not guilty verdicts, thousands of residents took to the streets of South Central Los Angeles and in front of LAPD headquarters nearly downtown, declaring "no justice, no peace."

Protesters in Los Angeles afterwards police found not guilty. (Photo from framework.latimes.com)

The acquittal came on the heels of Judge Joyce Karlin'due south judgement of probation and customs service for Korean merchant Sunday Ja Du after she killed Latasha Harlins, an African American teenager. Karlin's leniency combined with the history of police shootings and brutality—most notably the 1979 police killing of xxx-nine-year-onetime African American Eula Mae Love and the 1988 gang sweeps known every bit Operation Hammer that resulted in the indiscriminate arrest of thousands of young African American men—reflected the racially discriminatory and unequal criminal justice system.

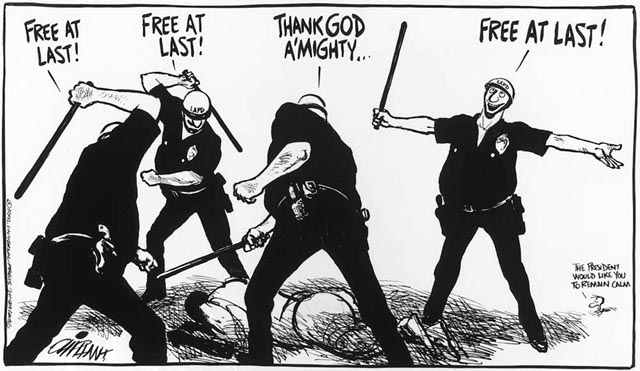

A disquisitional political cartoon past Pat Oliphant depicting LAPD police force beating Rodney Rex, c1992. (Library of Congress)

As i Inglewood Claret gang member told the author-historian Mike Davis: "my homies be shell like dogs by the police every day. This riot is all nearly the homeboys murdered past the police, near the niggling sister killed past the Koreans, about twenty-seven years of oppression. Rodney King simply the trigger."

The uprising also occurred inside the context of an economic recession that hit African Americans and Latinos particularly hard. Southern California lost 70-yard manufacturing jobs between 1978 and 1982 and another v-hundred-thousand jobs during the recession of the belatedly 1980s and early 1990s. Unemployment rates for blacks in 1992 hovered between forty and l percent and a poverty charge per unit of over thirty pct.

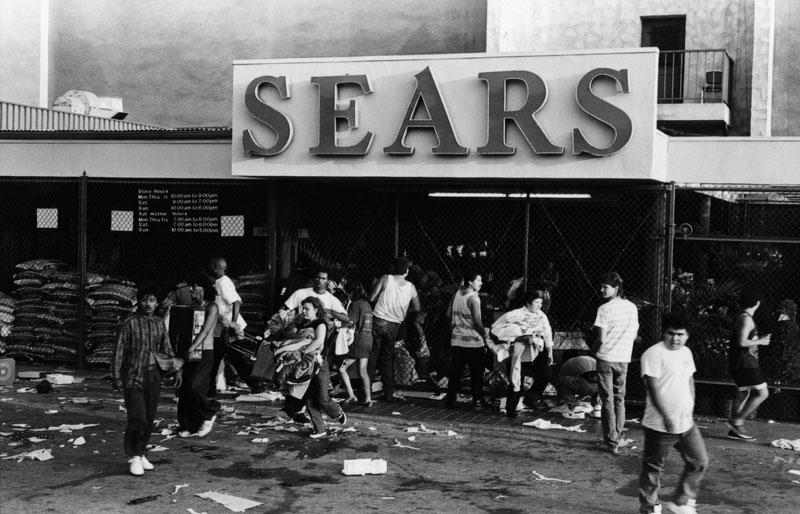

In the days after the verdict, looting and called-for engulfed vast swaths of the urban center. Information technology reached Koreatown, Hollywood, and parts of the San Fernando Valley virtually thirty miles away from the predominantly African American neighborhood of South Central where the uprising began.

Fires during the 1992 Los Angeles rebellion. (Photo by Gary Leonard, Los Angeles Public Library)

Onlookers lookout man every bit a building burns, 1992. (Photo by Gary Leonard, Los Angeles Public Library)

Fire fighters try to put out the burning La Mancha shopping center, 1992. (Photo by Gary Leonard, Los Angeles Public Library)

In contrast to the urban uprisings of the 1960s, this was a multiracial rebellion. Studies found that 50.6 percent of those arrested were Latino and 36.ii percent were African American. Many of the targets of violence were Latino immigrants—or perceived immigrants—and Korean shopkeepers.

City officials and LAPD commanders were unprepared for the violence despite Chief of Police Gates's merits that "no i knows how to handle a riot amend than I do." After the initial episodes of violence, nonetheless, Gates attended a fundraiser with opponents of police reform in the posh West Side neighborhood of Brentwood rather than organizing his section's response.

As officers retreated from the areas where violence had cleaved out, such as the infamous intersection of Florence and Normandie, the uprising accelerated and the city spun out of command.

Looting during the Los Angeles rebellion, 1992. (Photograph by Gary Leonard, Los Angeles Public Library)

Annexation during the Los Angeles rebellion, 1992. (Photo past Gary Leonard, Los Angeles Public Library)

Media outlets, police enforcement officials, and politicians portrayed participants every bit criminals without legitimate grievances. President George H. W. Bush blamed the violence on gang members and criminals. In a public accost to the nation, President Bush declared the violence was "not about ceremonious rights" or a "message of protest," but "the brutality of a mob, pure and unproblematic."

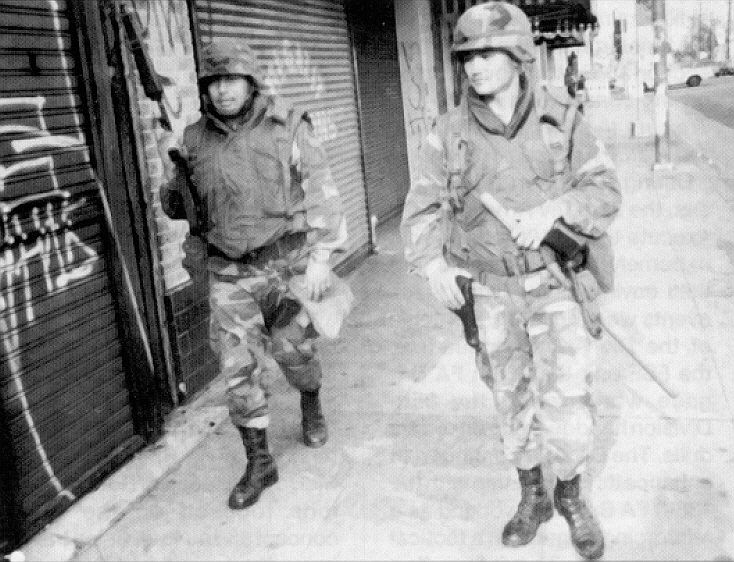

By framing the uprising as one of lawlessness, criminality, and illegality, officials legitimated ambitious policing, mass abort, and incarceration. Only first the LAPD required federal reinforcements. It took over 20,000 police force enforcement and war machine forces to end the ceremonious unrest, which resulted in sixteen,291 arrests, 2,383 injuries, at least 52 deaths, 700 businesses burned, and about $ane billion in damage.

One of around 700 burned shops in the aftermath of the Los Angeles rebellion, 1992.

Destroyed cars and store fronts, 1992.

Cooperation between local and federal law enforcement agencies also led to the arrest, detention, and deportation of undocumented immigrants. Most-four hundred INS agents worked with the constabulary and conducted dragnet sweeps in the predominantly immigrant Pico Union neighborhood. Of the 16,291 arrests, some estimated that 1,240 were undocumented immigrants, many of whom were handed over to the INS for immediate deportation. Such cooperation suggested the LAPD had violated its stated policy of not making arrests based on immigration status.

When the violence ended, Mayor Bradley appointed erstwhile CIA and FBI director William Webster to atomic number 82 yet some other committee to study the LAPD's response to the civil unrest. The commission focused on the LAPD'southward lack of training, poor intelligence, and inability to control the uprising. Finding new ways to mobilize police power and "rapid containment" took precedence over an investigation into the roots of police-community conflict.

Soldiers from the California Ground forces National Guard patrol the streets of Los Angeles, 1992.

After 160 days of investigation, neighborhoods meetings, and interviews with police officers the committee released its report, "The City in Crisis," on Oct 21, 1992. Instead of interrogating police practices and the criminal justice system that produced the conditions of the unrest, however, the report's recommendations focused on the ways that law enforcement could control future civil unrest.

While Mayor Bradley promoted economic evolution and individual investment through the not-profit system Rebuild L.A. every bit the solution to the city'south woes, punitive solutions meant to ensure the restoration of police-and-order prevailed equally the dominant response to the unrest.

Soldiers patrolling Los Angeles by vehicle (left), and on pes (right), 1992.

City and law officials likewise vied for federal criminal justice grants that linked social spending to funding for law enforcement. President Bush provided federal funds to help the city rebuild and made Los Angeles a target city for his administration'southward principal crime prevention program, Operation Weed and Seed, which integrated social service measures with increased spending for the police.

Mired in controversy, chief Gates resigned on June 30, 1992. The Lath of Police Commissioners appointed Willie Williams, a proponent of community policing, as the start African American chief of the LAPD.

Hopes that Williams would atomic number 82 a new era in the policing of Los Angeles were brusk-lived.

The Board of Police Commissioners refused to reappoint Williams for a second term in 1997 afterward personal scandals and opposition from rank-and-file officers. Community policing initiatives did little to shift controlling over the nature of policing to residents. The LAPD also became embroiled in another controversy during the Rampart corruption scandal in the tardily-1990s, which led to a federal consent prescript requiring Department of Justice oversight of the section.

Public safe funding through the 1990s also connected to support punitive policies focused on arrest and incarceration. California passed one of the nation'south strictest iii strikes laws in 1994 requiring life sentencing for a 3rd arrest for the nigh minor of infractions, leading to a rise in incarceration and a vast expansion of California's prison population.

Sign reading "Stop the Violence; All Men Were Created Equal," posted in Los Angeles during the aftermath of the rebellion, 1992.

The 1992 Los Angeles rebellion has meaning resonance for the current moment. Race, crime, and justice go along to exist central to debates about full inclusion and citizenship in American society.

Reflecting on the 1992 rebellion reveals how the reliance on punitive policies created hostility between the police and inner urban center residents, fed mass incarceration, and contributed to urban unrest. It demands an interrogation of the means law enforcement officers and the criminal justice system not merely proceed to resist efforts to ensure greater accountability and oversight but also how they police the boundaries of equality and full inclusion in American society.

Learn more about the L.A. Riots:

· Abu-Lughod, Janet L. Race, Space, and Riots in Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles (New York: Oxford Academy Printing, 2007)

· Cannon, Lou. Official Negligence: How Rodney King and the Riots Inverse Los Angeles and the LAPD (Bedrock: Westview Press, 1999)

· Davis, Mike. "Who Killed Los Angeles? A Political Autopsy." New Left Review 197 (1993): iii–28.

· Independent Commission on the Los Angeles Police Department, "Report of the Independent Committee on the Los Angeles Constabulary Section," (Los Angeles: The Commission, 1991)

· Stevenson, Brenda. The Contested Murder of Latasha Harlins: Justice, Gender, and the Origins of the LA Riots (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).

· Webster, William H., and Hubert Williams. "The City in Crunch: A Report past the Special Advisor to the Lath of Police Commissioners on the Civil Disorder in Los Angeles." Los Angeles, Oct 21, 1992.

Source: https://origins.osu.edu/milestones/may-2017-1992-los-angeles-rebellion-no-justice-no-peace?language_content_entity=en

0 Response to "in what ways did the rodney king event contribute to police reform"

Post a Comment